Text: Jens F. Laurson

The text was published in edition 3 (06/25).

Reading time 4 Min.

Kullervo: Sibelius’ Symphony No. 0

The proto-Symphony Kullervo is the Cinderella among Jean Sibelius’ orchestral pieces. A broad, bold creation shaped by the composer’s and his country’s desire for independence. After successful performances, Sibelius withheld this early work during his lifetime. In the past fifty years, however, Kullervo has undergone a steady revival. It is now regarded as a symphony “inter pares” with its seven numbered ones – his “Symphony No.0”, a bit like Anton Bruckner’s.

Independence Symphony. Epic drama. Secular cantata. When Jean Sibelius completed his symphonic poem Kullervo, Op. 7, for soprano and baritone solo, male choir, and orchestra in 1892, this five-movement, seventy-minute monolith – the longest work he would ever compose – appeared seemingly out of nowhere. Much like Béla Bartók’s Bluebeard’s Castle, an early masterpiece with no prior model, Sibelius had, in a single stroke, not only created a musical language of his own – but one that was a strikingly new and unmistakably Finnish”.

Let us return to the beginning: Finland had only recently emerged from 500 years of Swedish dominance, only to become a semi-autonomous Grand Duchy under the Russian Empire in 1809. Swedish remained the official language; most people spoke Finnish – but what “Finnish” meant had yet to be defined. Key figures in this identity-building process included poet Johan Ludvig Runeberg, philosopher Johan Vilhelm Snellman, doctor and author Elias Lönnrot, who compiled and published the Kalevala, Finland’s national epic. Sixty years later, Sibelius would provide its soundtrack.

Born as Johan Julius Christian Sibelius in Hämeenlinna, north of Helsinki, he grew up bilingual and was called “Janne” or “Sibbe.” He took the stage name 'Jean' from a business card belonging to a traveling uncle. His native language was Swedish, and he attended a Swedish-speaking primary school, but took private Finnish lessons to qualify for the Finnish Normal School.

As a composer, Sibelius was largely self-taught – or at least eager to appear so. In Helsinki, he enrolled in both law studies at university and music at the conservatory. There, the accomplished violinist met future collaborators: Robert Kajanus (orchestra founder, conductor, composer), Martin Wegelius (founder of the conservatory), Karl Flodin (critic), and Ferruccio Busoni (a year younger, already a faculty member). In spring 1889, Sibelius completed his courses at the conservatory – now the Sibelius Academy, renamed during his lifetime. Two scholarships led him to Berlin and then Vienna. In Berlin, he composed a piano quintet and became engaged to Aino Järnefelt while visiting home. In Vienna, he met Johannes Brahms (unimpressed, as always) and attended a Johann Strauss concert while sitting next to Bruckner. After hearing Bruckner’s Third Symphony, Sibelius wrote euphorically to his fiancée: “The best living composer.”

Amid lively local nights out, Sibelius also composed several early, unpublished works in Vienna – including Overture in E major and a ballet scene. Already at this stage, he conjures a beautifully romantic, if somewhat conventional sound – yet there is little, if anything, that hints at the distinctive style he would later develop. Still, Kullervo didn’t emerge from thin air: In Berlin, Sibelius heard Tannhäuser and The Mastersingers of Nuremberg. Although he positioned himself early as an anti-Wagnerian he was nonetheless profoundly impressed by the expressive scope Wagner´s music offered.

Sibelius attended the performance of the Finnish composer and conductor Kajanus when he conducted his own work Aino – a symphonic poem for choir and orchestra based on the Kalevala (!) – at the podium/conductor´s stand of the Berliner Philharmoniker. Sibelius denied Aino’s influence on Kullervo – yet began composing his own choral work based on the Kalevala shortly thereafter. A coincidence? In Vienna, he also experienced Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony under Hans Richter – an event that intensified his longing to compose a vocal symphony. In Porvoo, in 1891, he met the runic singer Larin Paraske and listened to her perform Karelian songs. These, in a sense, provided him with the grammar for a new Finnish musical language – even though Sibelius never directly quoted folk songs in his compositions.

That Sibelius, himself half-orphaned, would choose the tragic orphan Kullervo as his subject comes as no surprise. Pursued by fate and sold into slavery, Kullervo unknowingly seduces his own sister (The Valkyrie!). As a result, she takes her own life. Kullervo goes to war, returns as a broken man, and throws himself onto his sword. No easy material – but ideal for a dramatic large-scale piece exploiting all the expressive resources of late Romanticism. Kullervo and his sister are sung by baritone and soprano; the male choir narrates the story in Finnish, darkly, in its own Finno-Ugric linguistic melody, with elemental force.

Despite difficult conditions – only the soloists were professionals, rehearsals were scarce, and Sibelius had never conducted a work of such scale – the 1892 premiere was a resounding success that became a defining moment in Finnish identity. Soon after, Sibelius was allowed to marry Aino: his triumph complete. But doubts quickly crept in. Critics criticized the lack of stylistic unity. Ever the sensitive self-critic, Sibelius withdrew the piece. A promised revision never came. Only in 1935, at the Kalevala’s centenary, was the third movement (Kullervo and His Sister) performed with Sibelius’s blessing; a full performance followed only in 1958 under Jussi Jalas, his son-in-law – by then, Sibelius had been dead for a year. The cautious rehabilitation began with Paavo Berglund’s 1970 recording.

Today, Kullervo is accepted for what it is: a fully-fledged symphony. A “Symphony No. 0” in the best Brucknerian sense – autonomous, monumental, epic. Here begins what we later recognize as “Sibelian”.

Kullervo is no student composition, no draft – but an eruptive, elemental statement of epic scale and singular tone, in a language that resonates even if one doesn’t understand it.

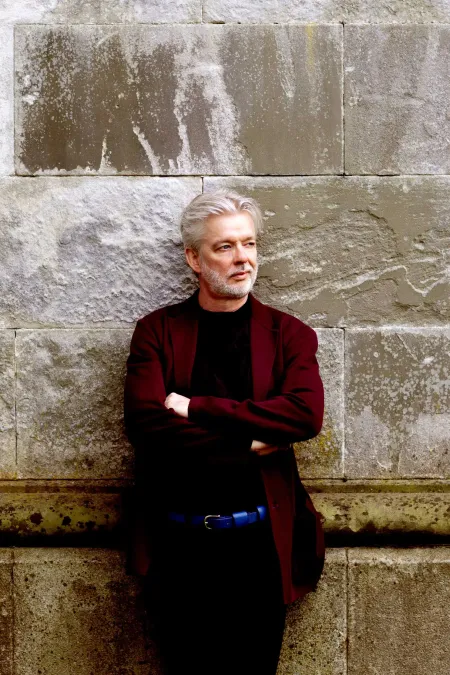

Star conductor at the stand: Under the direction of Jukka-Pekka Saraste, the Finnish YL Male Voice Choir, the men of the Prague Philharmonic Choir, and the Bregenzer Festspiele Choir bring the dramatic power of Kullervo to life.

Jukka-Pekka Saraste

Wiener Symphoniker

Sebastian Fagerlund

Drifts für Orchester

Jean Sibelius

Kullervo for soprano and baritone solo,

male choir, and orchestra, op. 7

27 July 2025 – 11.00 a.m.

Festspielhaus, Großer Saal