Florian Amort led through the interview.

The text was published in edition 1 (11/24)

Reading time 6 Min.

Personalities in oils and acrylics

Paintings by artist Vivian Greven accompany the productions of the 2025 festival summer

The artist Vivian Greven in her studio.

Theater is a place where people communicate across borders – a space where emotions, empathy and cultural identity blend together. The stories told onstage, and the sounds of the musical theater allow us to discover different times, cultures and perspectives. Do you also want to tell stories with your paintings?

Vivian Greven: While I went to the academy of arts, I also pursued English and American studies. I’m interested in the stories that affect and form us. I am fully convinced that we only become who we are because of what we tell each other. My paintings take up this thought, but I don’t tell stories in the traditional way. Instead, the subjects of my paintings carry their own stories, which act as references over centuries. A painting is not a picture book; instead, it’s like a personality that can be encountered on a different level. This level is rather intuitive and uses images to speak to our internal memory space, beyond rational reasoning.

There are two prominent imageries in your Oeuvre: The Greek and the Roman mythology with its often violent, male-dominated stories on the one hand, and femininity in all its physical and emotional facets on the other hand. What do you like about these quite contrary topics?

That’s a very interesting observation. If my paintings say something about being a woman, then it is me expressing my female view. But what is even more important for me is the essence of what it means to be human. My paintings show what it is like to be a human being in a body and inhabiting this body. That is also what fascinates me most about mythological motifs, but I think about this aspect over the times. I often use the stories of Narcissus and Echo or Cupid and Psyche, for example, because they deal exactly with this idea: the idea of a soul that manifests itself in a physical form. I want to find out how this soul encounters others, what happens when they blend together, close themselves off or even disperse. These psychological questions fascinate me and that is what I analyze in my paintings and investigate in depth.

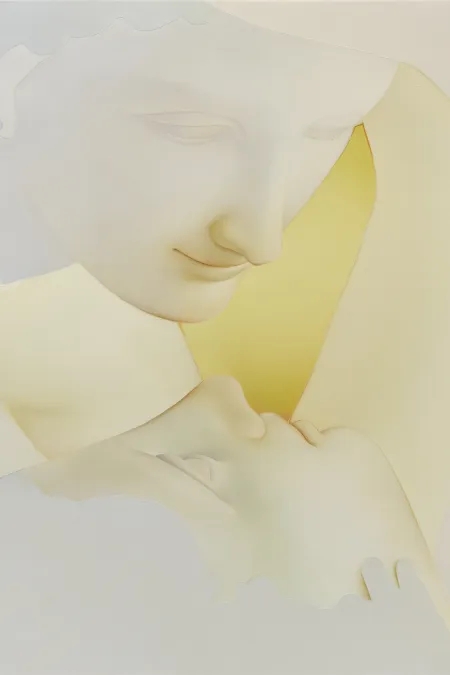

Some motifs inspire you to create an entire series, but the individual paintings always vary in some way. For George Enescu’s Œdipe we quickly agreed on Area III. We can see the head of a man holding another person in his arms – however, in this version, the person is almost dissolved, with only the contour remaining.

Vivian Greven: Area III, 2018, Bildmotiv für Œdipe

Courtesy of the artist und Kadel Willborn, Düsseldorf; Foto: Ivo Faber

The painting was inspired by one of Antonio Canova’s sculptures, in which Cupid and Psyche meet each other. Cupid holds Psyche in his arms, in a moment of anticipation and being able to see each other – an encounter on an inner level.

I called this series Area because it is about the space between the two: a space that separates them while also questioning how this space feels in the moment of the encounter and how it can be bridged. In Area III, we see Psyche herself becoming an “area”, she begins to dissolve in the encounter with Cupid, thereby losing her physicality. Here, skin is no longer a membrane, but merges into the dissolution of the image, becomes a part of the composition.

After Oedipus had blinded himself, he wandered around for years until the Gods showed mercy and led him back into the light. How is this connected with Cupid and Psyche?

The story of Cupid and Psyche also deals with the concept of seeing: What does it mean to be able to see each other with your own eyes – or not being able to see? Cupid doesn’t want Psyche to see him, but Psyche decides that she wants to see him – a decision that results in death. The moment we start objectifying others, part of our connection dies.

Another painting that also plays with light is O, which we selected for Tero Saarinen’s work Borrowed Light. How does this painting differ from Area III?

Vivian Greven: Vivian Greven: O, 2017, Bildmotiv für Borrowed Light

Courtesy of the artist und Kadel Willborn, Düsseldorf; Foto: Ivo Faber

O is part of the same group of motifs, but we view the scene from a different perspective. While in Area III, as viewers, we become part of the dissolution, in O, we perceive the scene more objectively, almost as if we were external observers. The way it is painted leans more towards the sculpture, and we can even see Cupid’s wings – a detail that strengthens the sense of distance and shifts the focus toward the form.

We talked about Carl Maria von Weber’s Der Freischütz for a long time, and, in the end, we agreed on the painting Aer I. On the one hand, because of the two hands forming a ball, and, on the other hand, because it shows two people trying but failing to touch each other. Max and Agathe also love each other but cannot just say yes to each other. First, Max must win a shooting contest.

In Aer I we see parts of two figures leaning onto each other; their hands engaging in a mysterious dialogue. They seem to be touching, but their hands point to something invisible between them. This puzzling tension is intentional – the painting raises a question: What lies between us? Is something keeping us from really coming into contact with each other? In the original sculpture, the figures hold a butterfly and try to tear out its wings. Without its wings, the butterfly, a symbol for the soul, remains a worm and reveals that, without love or a god, so Cupid, we are just worms on earth. I left out the butterfly in my version to open the question even more: Who are we and what really lies between us?

Another painting that shows two people engaged in communication is Vira V. We see two heads intimately leaning together. It is a good fit for Study for Life, a piece that resulted from the deep friendship between choreographer Tero Saarinen and composer Kaija Saariaho and deals with topics such as lifelong learning and affection.

The initial motivator for this series was the idea of breathing and the exchange of aerosols. When people approach each other, an exchange happens simply because both of them breathe – you absorb the other person and transfer information, consciously or unconsciously. That’s how dialogues that cross physical borders arise. Although the heads seem to be separated, they are connected with each other on an invisible level. This series also uses reliefs and the paintings are three-dimensional, which makes the exchange almost palpable. The idea is, that the viewer is dragged into the exchange. It is a symbolic play with forms, but ideally, that’s what my paintings do: they touch those that look at them and also become part of them.

The motif group Crac could be seen as the complete opposite. We agreed on Crac IV for Ferdinand Schmalz’s dystopian richtspiel bumm tschak oder der letzte henker. We see two people, but there is space between them. You continued this series after a longer pause. Why?

Vivian Greven: Crac IV, 2022, Bildmotiv für bumm tschak oder der letzte henker

Courtesy of the artist und Kadel Willborn, Düsseldorf; Foto: Ivo Faber

I like to let my works rest until a new aspect that I want to look at more closely comes up. Crac touches on the foundations of my artistic work: What does it mean to be human? When am I alone, when am I with somebody, when do I become one with the others? These are questions that accompany us our whole life and the paintings deal with them in depth. Crac IV shows two people tightly embracing each other but not completely touching each other.

But the space between them, this break, isn’t always painful; it can also create room for light, where colors that originate in the painting itself burst open. This series has its own coloring. They are inverted, so to speak, the light is reversed – it’s an attempt that plays with the idea of x-rays. I don’t look at the body through external light and shadow but reverse the relationship. Therefore, the figures look like ghosts. In this case, internal observations play an important role; the question of what happens inside of these two people when they touch each other.

Let’s talk about physical contact. The title of the series itself, )(, plays with the idea of a kiss between two people. We chose Number III of this series for Gioachino Rossini’s La Cenerentola, in which Cinderella meets her prince charming.

This series radically goes back to the essentials – the touch of two lips. There is no narrative. Instead, we focus on the essence of this moment. This creates somewhat abstract paintings. We see a landscape of lips with caves reminding us of a desert. With these depictions I always ask myself the question: What does it mean to be on earth? When are we free of ourselves and can change into something else? Will we end up in the deserts or the skies? When am I allowed to leave myself?

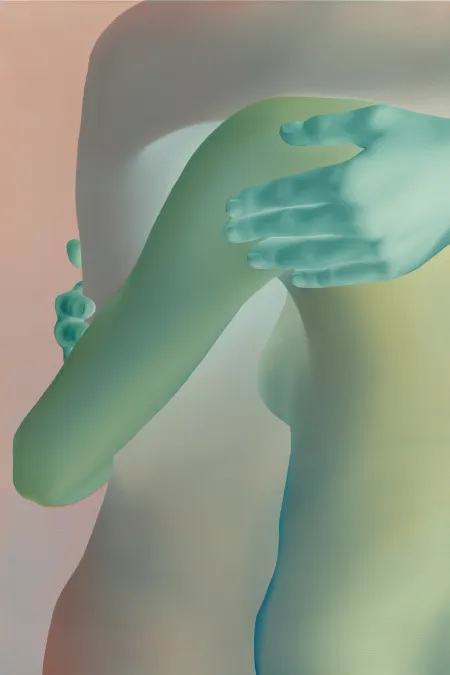

Qulla V shows a woman’s torso with her hand on her heart. We agreed on this painting for Emily – No Prisoner Be, which is a musical journey into the world of Emily Dickinson.

This painting refers to touching oneself. Putting one’s own hand on one’s chest is a very symbolic gesture and says: I feel. If you look at it more closely you will find a hole in the painting that reveals the canvas. Again, it’s about the existential question: Who am I? This question turns the hole into a symbol. I can see the external, but something else could be hiding underneath. The painting also raises a question about projections. That’s the connection to the story of Cupid and Psyche. It’s nice to see and identify the figure, the sculpture. But it turns out to be an illusion, because at the exact place where it touches itself, the surface begins to dissolve. What do we see when we look beyond the projections? That’s what I desire: to create a space where projections dissolve and real encounters are possible.

More about Vivian Greven and her work

can be found on her website: https://www.viviangreven.de/ and her social media channels.